Every year, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) adds hundreds of new words to the English language. It also updates entries for existing words where the definition has been added to or the word re-purposed. (Here is the most recent new word list). The English language is constantly evolving and new words enter the lexicon all the time. They come to prominence in a range of ways but, predominantly they emanate from a cultural environment (recent example: chillax), from popular entertainment (recent example: bucket list, which did not exist before the term was coined by 2007’s film of the same name), or from technology (recent example: blockchain).

Thousands of new words are considered every year by the OED. For a new word to be awarded a place in the dictionary, it must first have spent time on the ‘watch list’ database. This is curated from a range of sources, which include the OED’s own reading programmes to submissions from the general public, and more recently from automated monitoring and analysis of massive databases of language in use.

New words are assigned to OED editors and they will conduct their own research to trace the development of the word. They will scour printed media archives, social media and other online usage such as forums, published books, and academic studies. When an editor has finalised the research and confirmed existence and history of the word and it is agreed that the word is in common (and sustained) usage, then a dictionary entry will be created for it and it becomes a legitimate part of our common language.

2020 will, of course, be forever remembered for the great pandemic brought about by the emergence of COVID-19 but subsquent generations may well be using words and terms that have entered common usage in the last six months. How many of us talk routinely of ‘furlough’ even though we first heard the word in March? How often did you slip ‘herd immunity’ into your office banter prior to this year? In fact, there is quite a list of words and phrases many have probably uttered for the first time this year.

Here are some:

R-rate – a pandemic mathemetical algorithm we can all now confidently calculate in our heads.

Self-isolate / self-quarantine – This has not neccesarily been a huge problem for teenage boys with extensive gaming systems in their bedrooms.

Shelter in place – means reaching the actual end of the available programming on Netflix and cautiously checking out what the BBC has to offer (nothing).

Social distancing – being able to practice what we all secrety crave anyway.

Herd immunity – just letting people catch it and let the chips fall where they may.

Furlough – how to stay on permanent holiday and still get paid.

PPE (personal protective equipment) – only a new term to people who don’t work in the NHS or construction.

Shielding – a perfect excuse for not dragging the kids to see the grandparents.

Track and trace – a fantasy app that will be ‘world beating’. Apparently.

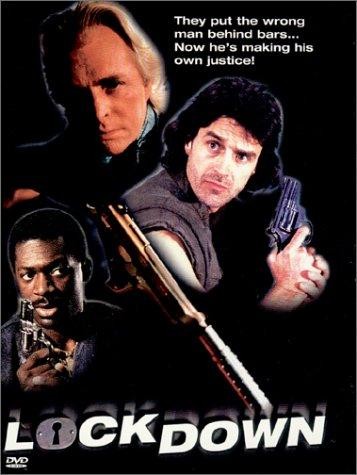

Lockdown – previously a prison movie.

Elbow bump – previously something that would have resulted in you getting punched in a pub car park.

Second wave – something at the beach?

Flatten the curve – a hairdressing term for problem hair,

Air bridge – I am running out of steam on coming up with nearly ironic or nearly funny explanations.

And of course, we have some examples of new slang:

Covidiot (noun): someone who stockpiles toilet paper, organises raves, ignores the requirement to wear a mask, or flouts physical distancing rules to sunbathe in the park. Alternatively, someone who goes to the park so they can take photos of people in the park and shame them for being in the park.

Doomscrolling (verb): obsessively consuming depressing pandemic news, searching for whatever the opposite of a dopamine hit is.

CovideoParty (noun): a virtual watching (of a film or play) party.

Quarantini and locktail (both nouns): alcoholic beverages you start on at about 11am.

Upperwear (noun) what you wear for Zoom calls on your upper half, while below you are in your pyjamas or underpants.

Pandemial generation (noun) pandemials are those children born in 2020.

How many of these words have found their way into your bids? It is extraordinary how quickly language takes hold and gains immediate traction across large swathes of the population. Of course, the ubiquity of social media now plays a big part in the spread of new words. Whereas new words and phrases might have taken root only locally, they now spread faster than... well, a pandemic. COVID related neologisms have been arriving faster than spam emails from deposed African princesses with money to hide.

When writing a bid for a customer, there was a time I would routinely include a Disaster Recovery Plan that would have a couple of lines on what would happen in the event of a pandemic. That was typically a cut and paste job, relegated to an appendix backwater of the bid. These days, it is pretty much front and centre, with much of the new phraseology worked into the narrative. Many companies have suddenly become highly expert at strategically placing hand sanitising stations and distributing face masks.

All of this being said, I am reminded of a time in the late nineties when the acronym ‘Y2K’ and the words ‘millennium bug’ were actual full-blown sections of every bid that went out of the door. That ceased to be the case on January 1st 2000, when planes seemed to have inexplicably remained in the sky and trains full of passengers had not all crashed into one another. Perhaps, just perhaps, there will be a time when the new pandemic language we have acquired will also fade quietly into the background. Let’s hope so.

Stay safe out there and thanks for reading.

Marcus Eden-Ellis

Bid Perfect | www.bidperfect.com

Copyright in this article text belongs to Bid Perfect. Reproduction is permissible under the caveat that credit is given to Bid Perfect as the source and copyright holder.

Comments

blog comments powered by Disqus